by Walter Olson

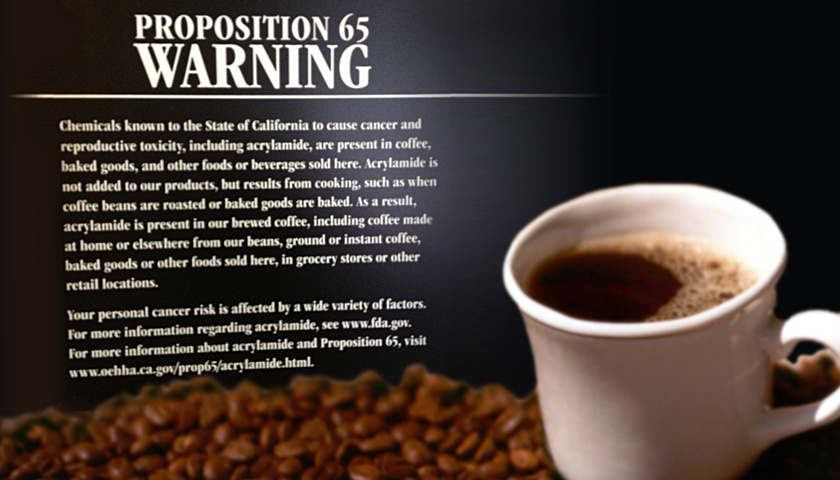

A judge in Los Angeles ruled Wednesday that Starbuck’s, Peet’s, and many other retailers face potentially massive liability under California law for not warning consumers that naturally occurring substances in roasted coffee beans can cause cancer, at least in lab animals. Absurd? Outrageous? Yes. But the scorn and outrage should be directed not at the judge but at the law whose terms he was required to enforce – Proposition 65, adopted by state voters through the initiative process in 1986 – as well as the lawyer-swayed California political system that still, more than 30 years later, is unwilling to address the measure’s gross flaws.

Almost everyone agrees that the over-proliferation of warnings makes it less likely that consumers will pay attention to real concerns.

Acrylamide is a naturally occurring substance formed when many foods are browned or otherwise subjected to high heat, including in many cases grilled burgers, fried chicken, bread, almonds, and potato chips. Like many other constituents of everyday life, it appears to cause cancer in some animals at high dosages. And that brings it under the terms of Prop 65, which has already led to a proliferation of warnings on and around thousands of common goods and services in California, from office furniture to hotel corridors to garages (car exhaust).

Almost everyone agrees by now that the over-proliferation of warnings makes it less likely that consumers will pay attention to those few warnings that actually flag notable risks. Although on paper the law provides exemptions for some risks that are not “significant” or are balanced by benefits, these have been hard for defendants to use in practice, and the coffee vendors were not saved by the argument that java overall provides (scientifically uncertain) net health benefits, which may even perhaps include net anti-cancer benefits, that outweigh the (also scientifically uncertain) risks.

What happens next? As the Post reports, “In addition to the warning signs likely to result from the lawsuit, the Council for Education and Research on Toxics, which brought the lawsuit, has asked for fines as much as $2,500 for every person exposed to the chemical since 2002, potentially opening the door to massive settlements.” And the financial shakedown value here is far from incidental; it’s the very motor that keeps the law going. Way back in 2001 – yes, Overlawyered has been covering this for nearly 20 years – I noted of the idealistic-sounding CERT, then involved in a suit against Starbucks over minute amounts of the Chinese herb ma huang in chai tea, and its lawyer Raphael Metzger:

While CERT is previously unknown, the same is not true of attorney Metzger, based in Long Beach, who runs a large “toxic-tort” practice whose website is publicizing the Starbucks action… “The constitutional right of Californians to pursue and obtain safety could be an untapped source of riches that plaintiffs’ attorneys should consider on behalf of their clients and the public,” Metzger wrote a while back in the San Francisco Daily Journal regarding the prospect of tort claims based on the California Constitution’s “inalienable rights” provision.

The financial shakedown occurring because of Prop 65 is far from incidental; it’s the very motor that keeps the law going.

Metzger is involved in CERT’s current coffee litigation as well. Meanwhile, the California political system, which listens carefully to the small industry of nonprofits and attorneys that make a living by filing suits, has been unwilling to do more than nibble around the browned edges of Prop 65’s famous irrationalities. The warnings of potentially chaotic results like today’s – like Prop 65 warnings in general – have gone ignored. Overlawyered has covered in detail both Prop 65 in general (including its use against scented candles, matches, brass knobs, light bulbs, playground sand, and billiard cue chalk) and acrylamide in particular.

– – –

Walter Olson is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute’s Center for Constitutional Studies.

First appeared at CATO.org and reprinted with permission from FEE.org